{jcomments on}Brian McLaren se boek Everything Must Change is ’n belangrike bron om te sien waarheen sekere Ontluikende Kerk-aanhangers op pad is.

McLaren stel homself bekend as ’n “committed follower of Jesus”. Hy word ook as ’n “evangelical” gereken. Time noem hom een van die 25 mees invloedryke “evangelicals” in die wêreld. Hy is bevriend met Bill Hybels van Willow Creek en Hybels het sover gegaan om die boek Everything must Change vir al sy ouderlinge voor te skryf. (Hybels het skynbaar heelwat kritiek oor sy vriendskap met McLaren gekry, maar Hybels se verweer is dat hy voortdurend mense na sy kerk toe nooi, met wie hy nie noodwendig oor alles saamstem nie. Gemeet aan onderstaande is dit onverstaanbaar dat Hybels sy boek aan enigiemand kan voorskryf, tensy hy tog maar in wese met hom saamstem.) McLaren is ook bevriend met Leonard Sweet en hulle deel hul entoesiasme vir die Ontluikende Kerk-gedagte.

’n Nuwe Jesus en ’n nuwe verstaan van God

McLaren gaan uit van die gedagte dat die Christendom Jesus verkeerd verstaan. Hy maak ’n groot saak uit vir wat hy noem die “reframing” (hervertolking) van Jesus. Hy wil wegbeweeg van Jesus as ’n persoonlike Verlosser, na Jesus as ’n Hervormer van die samelewing. Dit is dus ’n tipe bevrydingsteologie. Hy noem die wêreld ’n selfmoordmasjien (’n uitdrukking wat Leonard Sweet aan hom voorgestel het). Hy roep ons op om nie meer te glo in die ou sienswyses (“framing stories”) oor Jesus nie, en om te glo in ’n nuwe verhaal van ’n liefdevolle God, wat mense oproep tot ’n nuwe lewenswyse van die liefde. In die proses, is dit duidelik dat hy belangrike pilare van die Christelike geloofsbelydenis uit die pad stoot:

And we have raised the possibility that Jesus’ message might be seen as an alternative framing story that, if believed, could save the system from suicide. To test this possibility, we will need to consider the possibility that “Jesus” as we have understood him has himself been domesticated and made part of the dominant framing story. For Jesus to save the system, we must first, in a sense, save Jesus by reframing him outside the confines of our dominant and largely unquestioned assumptions. (bl. 73)

Brian McLaren toon baie begrip vir ateïste se kritiek op die God van die Bybel. Hy haal Thomas Paine (1795) soos volg aan (my onderstreping):

Whenever we read … the cruel and tortuous executions, the unrelenting vindictiveness with which more than half the Bible is filled, it would be more consistent that we call it the word of a demon than the word of God. It is a history of wickedness that has served to corrupt and brutalize humankind. And, for my own part, I sincerely detest it, as I detest everything that is cruel. (bl. 153) (Kyk egter Om God en die Bybel te verstaan, Is the Bible ‘evil’? en Countering the Critics Questions and Answers onder “How can the bloodshed inflicted upon the Israelites’ enemies in the OT be reconciled with an all-good God? What about slavery? Or atrocities committed by professing Christians?”)

Hy haal ook vir Sam Harris, ’n leidende Amerikaanse ateïs, soos volg aan (my onderstreping):

There’s no document that I know of that is more despicable in its morality than the first few books of the Hebrew Bible. Books like Exodus and Deuteronomy and Leviticus, these are diabolical books. The killing never stops. The reasons to kill your neighbor for theological crimes are explicit and preposterous. You have to kill people for worshipping foreign gods, for working on the Sabbath, for wizardry, for adultery. You kill your children for talking back to you. It’s there and it’s not a matter of metaphors. It is exactly what God expects us to do to rein in the free thought of our neighbors. (bl. 153)

McLaren vervolg:

But Harris doesn’t easily let Christians off the hook by using a meek and mild Jesus as an exemption from biblical violence. Yes, “in half his moods” Jesus speaks about peace and compassion, Harris says, but “there’s another Jesus in there. There’s a Jesus who’s just paradoxical and difficult to interpret, a Jesus who tells people to hate their parents … coming back amid a host of angels, destined to deal out justice to the sinners of the world …” (bl. 153)

Harris can’t be blamed for seeing a “moody” Jesus, peaceful one minute and vindictive the next, because the religion that bears his name has shown precisely this bipolarity through history: for every courageous and peaceful saint willing to live and die in the spirit of Saint Francis, there have been any number of bishops and theologians willing to justify the killing and torture of heretics, to bless unjustifiable wars, and to incite mistrust and prejudice toward unbelievers. For every Martin Luther King and Desmond Tutu proclaiming the Jesus who rode on a donkey and spoke of peace, there have been plenty who proclaim a different Jesus, well armed and dangerous. (bl. 154)

Let daarop dat hy in onderstaande nie meer ander aanhaal en dan moontlik net gedeeltelik met hulle saamstem nie, maar dat hy nou sy eie opinies direk weergee:

… More and more of us are discovering a fresh vision of a Jesus who seems less moody, irrational, and bipolar, and more consistent, focused, courageous, subversive, and brilliant. (bl. 155)

Dit wil lyk of Brian McLaren sy oplossing vir die wrede God/god van die Ou Testament soek in die persoon van Jesus, maar dan ’n Jesus wat ons moet hervertolk. Hoe verder mens hieronder lees, hoe duideliker word dit dat hy ’n “ander Jesus” verkondig.

To be a follower of Jesus in this light is a far different affair than many of us were taught: it means to join Jesus’ peace insurgency, to see through every regime that promises peace through violence, peace through domination, peace through genocide, peace through exclusion and intimidation. Following Jesus instead means forming communities that seek peace through justice, generosity, and mutual concern, and a willingness to suffer persecution but a refusal to inflict it on others. To follow Jesus is to become an atheist in regard to all bloodthirsty, tribal warrior gods, and to become a believer in the living God of grace and peace who, in Christ, sheds God’s own blood in a manifestation of amnesty and reconciliation. (bl. 159)

Die verlossing deur Jesus

Die verlossingswerk van Jesus sentreer vir ons in die eerste plek rondom Sy kruisdood ter wille van ons sondes. Jesus self noem dit ’n losprys (Matt. 20:28). McLaren noem nie eers die moontlikheid dat Jesus ons gered het van die gevolge van ons eie sondes nie en praat smalend van dié soort verlossing. Hy stel nuwe dinge voor wat ons moet ontdek waarvan Jesus ons glo verlos het (my onderstreping):

In searching for a better framing story than we currently proclaim, Christians like myself can discover a fresh vision of our religion’s founder and his message, a potentially revolutionary vision that could change everything for us and for the world we inhabit. We can rediscover what it means to call Jesus Savior and Lord when we raise the question of what exactly he intended to save us from. (His angry Father? The logical consequences of our actions? Our tendency to act in ways that produce undesirable logical consequences? Global self-destruction?) The popular and domesticated Jesus who has become little more than a chrome-plated hood ornament on the guzzling Hummer of Western civilization, can thus be replaced with a more radical, saving, and, I believe, real Jesus. (bl. 6)

Die wederkoms van Jesus en die ewige oordeel

McLaren ontken die werklike wederkoms en die ewige oordeel van God. Sy idee van Jesus se wederkoms is dat die mensdom sodanig sal ontwikkel dat die goeie die bose, en liefde straf, sal oorwin – daarom kan daar nie toekomstig ’n ewige oordeel wees nie (my onderstreping):

… many of us have been increasingly critical in recent years of popular American eschatology in general, and conventional views of hell in particular. Simply put, if we believe that God will ultimately enforce his will by forceful domination, and will eternally torture all who resist that domination, then torture and domination become not only permissible but in some way godly. The implications for, say, military policy (not to mention church politics) are not hard to imagine.

The phrase “the Second Coming of Christ” never actually appears in the Bible. Whether or not the doctrine to which the phrase refers deserves rethinking, a popular abuse of it certainly needs to be named and rejected. If we believe that Jesus came in peace the first time, but that wasn’t his “real” and decisive coming – it was just a kind of warm-up for the real thing – then we leave the door open to envisioning a second coming that will be characterized by violence, killing, domination, and eternal torture …

If we remain charmed by this kind of eschatology, we will be forced to see the nonviolence of the Jesus of the Gospels as a kind of strategic fake-out, like a feigned retreat in war, to be followed up by a crushing blow of so-called redemptive violence in the end. The gentle Jesus of the first coming becomes a kind of trick Jesus, a fakeme-out Messiah, to be replaced by the true jihadist Jesus of a violent second coming. (bl. 144)

… The Jesus of one reading of the Apocalypse brings us to a grim resignation: the world will get worse and worse, and finally this jihadist Jesus will return to use force, domination, violence, and even torture – the ultimate imperial tools – to vanquish evil and bring peace. But exactly what kind of victory and peace are we left with when domination, violence, and torture have won the day? This version of Jesus brings us to a kind of fatalism that sees the future predetermined and our actions incapable of altering the divinely preset outcome. And it sees domination, violence, and torture as, the eternal legacy of God’s creative project.

The Jesus of the emerging reading we have considered in the preceding chapters tells us the opposite: that good will prevail by peace, love, truth, faithfulness, and courageous endurance of suffering, and that domination, violence, and torture are among the things that will be overcome. (bl. 146)

Die koninkryk van God – net op aarde

Brian McLaren het ’n visie vir ’n eutopia (’n goeie plek), of ’n nuwe plek op aarde. Hy beskryf dit soos volg (my onderstreping):

Many believe the apocalyptic vision of the New Testament is not intended to give us this kind of hope within history. They might point to the vision of the new Jerusalem (Revelation 21), which, they say, is intended to give us a vision of the destruction of our dynamic space-time universe and its replacement, beyond history, with a timeless, static state called “eternity” or “heaven” where everything is absolutely perfect. Increasing numbers of us disagree with this assessment.

As we discussed in chapter 18, more and more of us see this eschatology of abandonment and despair to be an example of the biblical story being rewritten to aid and abet the dominant system. We believe the vision of the new Jerusalem, like all prophetic visions, seeks to inspire our imaginations with hope about what our world can actually become through the good news of the kingdom of God.

In this emerging view, the “new heaven and new earth” (Revelation 21: 1) means, not a different space-time universe, but a new way of living that is possible within this universe, a new societal system that is coming as surely as God is just and faithful …

The new Jerusalem represents, then, a new spirituality, a new way of living in which the sacred presence of God is integrated with all of life and not confined to temples (v. 22) – a vision which Jesus saw as real in his day (John 4:21-24). We haven’t evacuated the dark earth for the light of heaven or eternity; no, the light of heaven has come down, come down to us, down to earth.

The extravagant language doesn’t describe a utopia (meaning a no-place) but a eu-topia, meaning a good place, a new-topia, meaning a renewed place. The message of the apocalypse is that the empire of Caesar, including the religious apparatus that sustains his system, will not last for ever, but that the empire or kingdom of this world (earth’s integrated political and economic and social systems, its principalities and powers, its societal machinery) will ultimately be transformed so it becomes “the kingdom of our Lord and of his Messiah, and he will reign for ever and ever” (Revelation 11:15). This is the coming of a new generation of humanity that Jesus embodied, demonstrated, proclaimed, and invited us to believe.

Yes, this is the end of the world – but not end in the sense of the discontinuation of our story; rather, it is the end in the sense of the goal toward which we move. Yes, it is the end of the world as we know it – a world dominated by suicidal machinery driven by a suicidal framing story. But it is the beginning of the world as God desires it, a new story, a new chapter, a new way. (bl. 297)

(Volgens die 2de wet van termodinamika brand alles uit – oor miljoene jare sal die son en ander sterre geen energie uitstraal nie en dan sal dit definitief die einde van enige lewe op aarde wees, tensy ’n bonatuurlike ingryping plaasvind (kyk Waar kom al die nuttige energie vandaan?). Dus wonder ’n mens wat McLaren glo gaan dan gebeur? En natuurlik mense wat doodgaan – waarheen gaan hulle?)

Hervertolking van Jesus

McLaren sê dat Jesus ’n politieke figuur was. Die titels Verlosser, Seun van God, Seun van die mens en Here, is almal titels waarmee Jesus die gesag van die keiser en die Romeinse Ryk uitgedaag het. Mclaren sien selfs die uitdrywing van demone deur Jesus as profetiese dade van Israel se bevryding van die Romeinse Ryk (bl. 98-99). Jesus het Homself dus in al sy optrede ten diepste teenoor die Romeinse Ryk opgestel. Die VSA funksioneer vandag as ’n ryk met dieselfde karaktertrekke as die van die Romeinse Ryk. Hy bespreek kapitalisme, die soeke na politieke mag, wapenmag en sekuriteit by die Westerse moondhede. Die volgelinge van Jesus (God se “beloved community”), se taak is om hierdie kragte aan te spreek:

This emerging view of Jesus – framed against the backdrop of empire and its narratives and counternarratives – makes possible a valid (I would even say a better) way to understand him, his life, his message.

From this viewpoint, when Jesus proclaimed his central message of the kingdom of God, he was proclaiming not an esoteric religious concept but an alternative to empire: “Don’t let your lives be framed by the narratives and counternarratives of the Roman empire,” he was saying, “but situate yourselves in another story … the good news that God is king, and we can live in relation to God and God’s love rather than Caesar and Caesar’s power” (bl. 90).

Ons opdrag

Brian McLaren stel die mensdom se opdrag soos volg. Let daarop dat die bestaande evangelie en Jesus se wederkoms (bestaande “framing stories” van Jesus), deel is van wat McLaren wil hê ons nie meer moet glo nie (my onderstreping):

… the Bible instead is the story of the partnership between God and humanity to save and transform all of human society and avert global self-destruction (bl. 94).

There is one great step we can take to dismantle the suicide machine and the framing stories that legitimize it: to stop believing in it, and to believe, in its place, a different story, the story of the kingdom of God.

The way to dismantle the suicide machine is to deny it the fuel on which it runs: confidence – confidence in its framing story. The way to create a generous, generative, and humane alternative society in place of the suicide machine is to believe the good news of the kingdom of God. (bl. 275)

Dit is baie duidelik dat McLaren vir hom ’n eie god skep wat inpas in sý wêreldbeeld. Dit is niks anders as oortreding van die tweede gebod nie: Eks. 20:4 : “Jy mag nie vir jou ’n beeld of enige afbeelding maak van wat in die hemel daarbo of op die aarde hieronder of in die water onder die aarde is nie.”

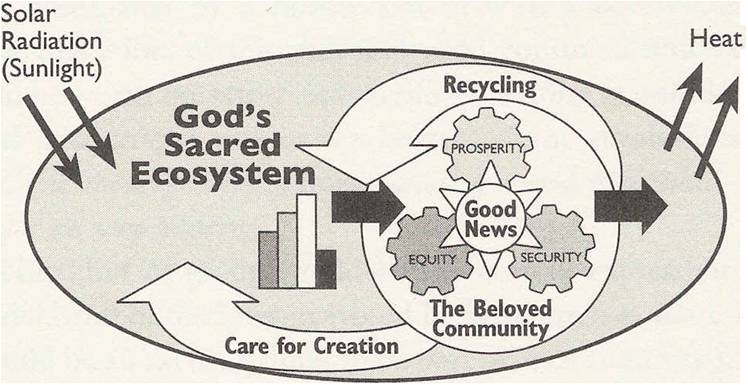

In die laaste hoofstuk: “Moving Mountains”, gee Mclaren ’n skematiese voorstelling (onder) van sy visie vir die toekomstige wêreld. Dit is die nuwe Jerusalem – die einde, waar sy idee van die Messias se koninkryk vir ewig en altyd sal bestaan (volgens sy vertolking van Op. 11:15). Geen wese wat ooreenstem met Jesus Christus van die Nuwe Testament sal oor daardie koninkryk regeer nie. Sommige van die goeie idees en beginsels van die Nuwe Testament, en vele meer wat intussen ontwikkel het en nog sal ontwikkel, sal egter wel dan bestaan.

Die probleem is dat baie van McLaren se idees, alhoewel dikwels in sagter formaat, deurskemer in baie van die ontluikende leiers se preke en uitlatings. My hoop is dat hierdie bespreking van McLaren se boek, meer predikers en lidmate se oë sal oopmaak om dit raak te sien.

_________________________

“I don’t believe making disciples must equal making adherents to the Christian religion. It may be advisable in many (not all!) circumstances to help people become followers of Jesus and remain within their Buddhist, Hindu or Jewish contexts … rather than resolving the paradox via pronouncements on the eternal destiny of people more convinced by or loyal to other religions than ours, we simply move on … To help Buddhists, Muslims, Christians, and everyone else experience life to the full in the way of Jesus (while learning it better myself), I would gladly become one of them (whoever they are), to whatever degree I can, to embrace them, to join them, to enter into their world without judgment but with saving love as mine has been entered by the Lord.”

– Brian McLaren uit sy boek More Ready Than You Realise (bl 80-81).

Kyk ook

- Christianity and McLarenism – Ten Questions and Ten Problems, deur Kevin DeYoung.

- More Ready Than You Realize – Evangelism as Dance in the Postmodern Matrix

- Rob Bell se Noomas